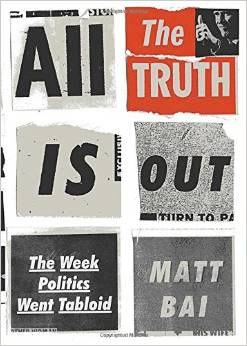

All the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid by Matt Bai, Alfred A Knopf, 2014.

All the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid by Matt Bai, Alfred A Knopf, 2014.

Yet another NPR-publicized book. If you’re of a certain age, the name “Gary Hart” conjures up one image, and one image only: of the smiling, mop-haired man in a “Monkey Business Crew” t-shirt with the beautiful woman on his lap. And that’s it. When that one picture hit the papers it was all over for a man who at that point was virtually a shoo-in to be the Democratic nominee for President in 1987. Nothing else mattered. He pretty much disappeared from political life.

However much you (and I) may deplore adultery (and whatever may have ultimately happened between Hart and Donna Rice, there was no doubt that he had had numerous affairs during his long but troubled marriage), it is fair to point out that with this one incident the rules of engagement between the press and political candidates changed.

Up until this time, reporters were expected to keep their mouths shut about any and all sexual escapades that they knew about in the lives of those they covered. Certainly JFK and LBJ were known for their womanizing, but no reporter would report, and no publisher would publish, a story about such things. On the one hand, discretion and decorum were preserved, qualities that are just about nonexistent in any type of press coverage today. On the other, the women involved were treated as objects to be hidden from public view, and a failure to keep your wedding vows wasn’t seen as any kind of character failure in the public arena. What changed the rules? All sorts of things, with the main factor being, as the book cover phrases it, “the relentlessness of the newly-born twenty-four-hour news cycle.” Bai frequently references Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, a classic on how media shapes perception that was published only two years before the Hart scandal.

I must admit that I did a little skipping here and there: Bai is very thorough. The ending chapter, in particular, gets a little tiresome. But most of the book speeds along, and Bai has interviewed just about everyone involved who’s still around, including Hart himself, and tracked down various old interviews and speeches that have never been digitally archived; he must have driven the good folks at the Library of Congress crazy. He knows what he’s talking about. (Interesting little busted myth: the story has always been told that Hart said to some reporters, “If you have questions about my personal life, just follow me around and see what I do” or words to that effect, and the reporters did just that, discovering Donna Rice. But actually that line was somewhat of a sarcastic throwaway in an interview that came out the same day that the scandal broke. Advance copies of the interview had been sent out to newspapers, and the line did make the reporters and editor wrestling with the story’s appropriateness feel more comfortable about going ahead and publishing, but Hart wasn’t quite as stupid about the whole thing as the myth makes him out to be. Not quite.)

If you’re interested in the American political process, or a study of human character, or you just like being let in behind the scenes at a turning point in history, read this book. (You knew I’d say that, didn’t you?)