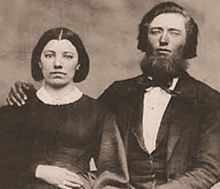

I said in an earlier post that I wanted to explore further the life of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s mother, Caroline, called “Ma” in the books. The more I’ve read about her the more fascinating she’s become. As I’ve re-read some of the Little House books, especially the first one, Little House in the Big Woods, I’ve been more and more impressed with how much sheer practical knowledge about survival both she and Pa had. I had thought originally that Ma had come from a pampered city life because of a passage that shows up in this first book about Ma’s best dress, her “delaine.” Pa has just come home from visiting his father to help with making maple syrup and says that there’s going to be a “sugaring off” party with a dance included.

Then she went on with her mending, but she kept on smiling. She said, “I’ll wear my delaine.”

Ma’s delaine dress was beautiful. It was a dark green, with a little pattern all over it that looked like ripe strawberries. A dressmaker had made it, in the East, in the place where Ma came from when she married Pa and moved out west to the Big Woods in Wisconsin. Ma had been very fashionable, before she married Pa, and a dressmaker had made her clothes.

The delaine was kept wrapped in paper and laid away. Laura and Mary had never seen Ma wear it, but she had shown it to them once. She had let them touch the beautiful dark red buttons that buttoned the basque up the front, and she had shown them how neatly the whalebones were put in the seams, inside, with hundreds of little crisscross stitches.

The key sentence is: “Ma had been very fashionable, before she married Pa, and a dressmaker had made her clothes.” So wouldn’t you wonder a bit about how this fashionable girl from the East with her fancy clothes ever married a decidedly non-city man and then suddenly knew how to do all this food preparing and preserving that I talked about in the last post? It never made much sense to me, and indeed this view of Ma is completely wrong. Laura is talking about the impression she had as a girl of her mother’s early life, and it’s pretty clear that Ma didn’t tell her the whole story. In reality, and I think these events are quite relevant to today because they show how resilient human beings can be, Ma came from an incredibly deprived background. Here’s what happened (as Monk would say):

Caroline was born in what is now eastern Wisconsin (so, that’s the “East” that Laura talks about) into the Quiner family. Her father was a trader, doing at least some of his business with the Native Americans in the area, sometimes traveling by land and sometimes by boat on Lake Michigan. It was on one of those boat trips that he was lost in a storm. Ma’s mother was left with five children and another one on the way, with no way to provide for them. One website dedicated to all things Little House says that:

Without the income from Henry’s trading, the family was left destitute and if it were not for help from Henry’s former trading partners among the local Native American tribes and charity from neighbors, the family may not have survived. Caroline remembered this dark time in her family’s history and learned from it. She learned that you have to make do with what you have and can’t take for granted that there will be food on the table or that someone who leaves will ever come back. (“About Caroline Ingalls [‘Ma’]”)

Eventually the mother moved her family to a 40-acre government land allotment and ended up marrying a farmer in the area. Caroline was nine; she had been five when her father was lost, just old enough to know what was going on. Her mother must have been what I call “a force of nature;” otherwise, even with the help she received, she would never have survived. But there was another force of nature at work also—there must have been. Who assisted that mother with her sixth childbirth? Who pitched in with all the “making do” mentioned in the quotation above? Why, Caroline did. She was the oldest child, and children grew up fast in those days. When I read about Ma’s cheese-making or hominy-manufacturing I was so puzzled. Who taught her all this stuff? Finding out the real story about her childhood gave me the answer. (Pa was no slouch as a child, either. We’re told that “When Pa was eleven years old he had done a good day’s work in the fields, driving a team.”)

And what about the delaine dress? (“Delaine” is a fine woolen material.) I’m going to postulate that it was actually Caroline’s wedding dress—no one in her situation wore a one-time-only, easily-soiled white dress. (Queen Victoria started that tradition; Caroline and Pa were married in 1860, 20 years after Victoria and Albert, but the white wedding dress tradition hadn’t penetrated to the wilds of Wisconsin.) She might very well have splurged on having a dressmaker make it, although Ma was no mean seamstress herself. There was a lot of bartering in those days; in one of the later books Laura worked at a seamstress’s shop in De Smet, South Dakota, and sometimes took part of her wages in fabric or other items. Ma might have done the same, doing plainer sewing to pay for the delaine. Or maybe she made hats; we’re told all about how she made “lovely hats” out of oat straw. Just when I think there can’t possibly be one more thing that woman knew how to do . . .

All this is to say that nothing would ever have been taken for granted in the Ingalls home, including, especially, the food on the table. And the people who provided it, too. Ma surely remembered waiting and waiting for her father to come back home after he’d drowned. And yet no displays of anxiety are recorded as being shown by her when Pa goes out hunting or on other trips. She must have perfected the art of hiding her feelings. There’s a lovely little scene in Big Woods when Pa says to Ma, “Nobody’d ever starve to death when you were around, Caroline.” “Well, no,” Ma said. “No, Charles, not if you were there to provide for us.” Isn’t that great? We’re told that “Pa was pleased” and that as he put his fiddle away he was “smiling and whistling softly to himself.”

Okay, that’s enough Ingalls nostalgia for one day. (Probably some of you reading this post are aware that the books and the actual historical facts don’t always match up perfectly, but I’m going to gently pass over that issue. Let’s just say that the narrative was “shaped” a bit and leave it at that.) I had planned for this post to write about how food was seen primarily as fuel and to describe how the farm women had to work so hard to provide food not only for their families but also for the work crews during “thrashing” season. (My dear father worked on a “thrashing crew” as a teenager, and my Aunt Martha, his sister, has talked before about how, while the crew was out in the fields the women were in the kitchen, whipping up the five meals a day that the crew needed to keep going.) But we’ll get to that next time.

Stay safe, stay well, and get the Little House e-books from the library.