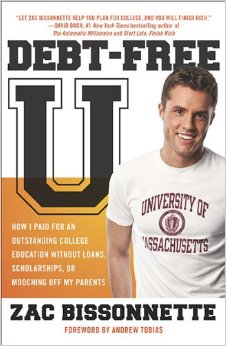

Debt-Free U: How I Paid for an Outstanding College Education Without Loans, Scholarships, or Mooching Off My Parents by Zac Bissonnette, Portfolio/Penguin 2010.

Debt-Free U: How I Paid for an Outstanding College Education Without Loans, Scholarships, or Mooching Off My Parents by Zac Bissonnette, Portfolio/Penguin 2010.

Even if you have no kids going to college, or you’re not a kid planning to go to college, you should read this book. (But you should also read it if you do fit into one of those categories.)

A couple of posts ago I wrote about Dinner: the Playbook, and I said that book wasn’t valuable so much for the recipes or the specific information about planning meals as it was in promoting a general outlook that says: “What can I do right now?” A proactive approach. Well, this is the same type of book, in that it contains principles that go far beyond making sound economic choices when it comes to college.

If everyone applied the advice given here to their lives as a whole, there would suddenly be a resounding lack of spending on luxury cars, or designer handbags, or houses twice as big as any fourteen people need. There would be hardly any credit card debt. The whole economy would collapse! (There’s probably not much danger.)

Before I get to the overall picture, though, I have to say that reading this book made me feel much better retroactively about Jim’s and my total refusal to get all of a doo-dah over Gideon’s college prospects during his junior and senior years of high school. Of course, a big reason for the lack of said doo-dah was that we were concentrating all of our energies and concern on just getting him to graduate, since he missed so much school because of his horrible sleep problems. (Hey, you can read all about that saga in chapter 8 of my book here and then, if you like what you read, you can order a copy of the entire book here.) Anyway, at some point during his senior year I did find myself thinking, “Everyone’s so worried about getting into a good college. Shouldn’t Gideon be sending in applications and watching the mail like everyone else?” And the answer, according to this book, is a resounding no.

So what’s the guy’s point? It’s simply this: Most people, parents and teens, choose a college for entirely the wrong reasons, and they’re helped along in this mistaken process by people who very much do not have the hapless student’s best interests at heart. Who are these people? Well, Bissonnette lists them: high school guidance counselors, college admissions officers, financial aid officers, and your family and friends. (Yes, even those last.) They all have an agenda. You need to choose what’s right for you and not be swayed by other people’s ideas about where you should go and what you should do. (I have to stop here and tell a joke. Two men were sitting in a doctor’s waiting room, and the first one said to the second, “I see that you’re a farmer. I can tell by the manure on your boots.” And the farmer said, “I see that you went to Harvard. I can tell by your class ring that I saw when you picked your nose.” Hey, don’t blame me! Blame my farmer relatives.) In other words, you can’t be swayed by peer pressure. That parent at the cocktail party being quizzed by a new acquaintance about where her son goes to college is just as subject to that insidious force as any teenager breathlessly striving after the right cool look to fit into the right cool group. It’s all the same thing. People are going thousands of dollars into debt, whether they be the parents or the students, because they’ve bought into the idea that getting into a high-ranked college, no matter how expensive it may be, is the only path to success in life. And yet . . . we all know, really, that it isn’t so. We all know the stories of people crashing and burning at the elite schools and very solid, successful people who went to schools no one has ever heard of.

Now, you may have specific reasons for going to a specific school, or type of school. Maybe you want your kids to go to a Christian college, or perhaps there’s a music or science or art program that you really like at one place. Those may be perfectly valid reasons for attending that college. The point is, when you’re making such a huge decision, you must not be swayed by a desire for prestige, a sales pitch, or the emotions of the moment. Just as people often buy a house or car (two other major financial decisions) for reasons that have nothing to do with how the item will actually work for them and/or whether or not they can actually afford it, people pick colleges for the most trivial of reasons. Here’s my favorite quotation from this book: “Please, please, please: do not allow your child to pick a college based on the way the light filters through the trees. Really. There is little reliable data to suggest that arboreal luminescence is a good predictor of college success” (135). If you can’t afford a small, private college, whether you’re a parent or a student, don’t visit small private colleges. Just as you shouldn’t walk into a Maserati showroom if you can’t afford one. Be tough! Think for yourself! (A story about people who didn’t follow that advice, some friends of ours who used to live outside Chicago: They had told their realtor that they didn’t want to live in a certain suburb, and they didn’t want to spend more than a certain price. So the realtor took them to see a house in the out-of-bounds area that cost too much. Did they tell her to go fly a kite? No. They bought the house. And then they were stuck with the big mortgage and the long commute that the house entailed. It was a beautiful house. But they should have said no.) I would close this book review by quoting the title of another book, this one by the great physicist Richard Feynman: “What Do You Care What Other People Think?”