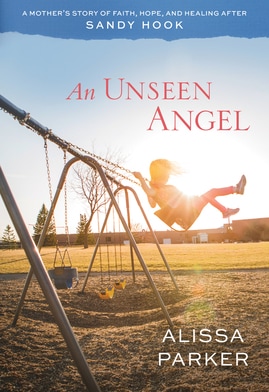

An Unseen Angel: A Mother’s Story of Faith, Hope and Healing after Sandy Hook by Alissa Parker, published by Shadow Mountain Publishers, 2017. Available through many sources; cover image is from Deseret Book, the only website that allowed me to copy it. Visit the book website at An Unseen Angel.

An Unseen Angel: A Mother’s Story of Faith, Hope and Healing after Sandy Hook by Alissa Parker, published by Shadow Mountain Publishers, 2017. Available through many sources; cover image is from Deseret Book, the only website that allowed me to copy it. Visit the book website at An Unseen Angel.

I had this cute post I was going to write today, about how Wednesday at noon is the start of my “work at home” section of the week, and that I’d decided to institute a little treat to mark that point since I can then spray on some perfume. We’re asked not to wear “strong” fragrances to Bible Study Fellowship meetings, on Tuesday and Wednesday mornings, and we are absolutely forbidden to wear any fragrances to Chorale rehearsals. Once I get home on Wednesdays, though, I can do what I want. Gretchen Rubin talks a lot about how we need to give ourselves treats, little indulgences that can add to our happiness but which won’t cause us more problems than they’re worth. (So my Reese’s peanut-butter cups don’t fit into this category.)

I got into the car and turned on the radio, as I almost always do, and caught the tail end of an interview on NPR with Alissa Parker, the mother of one the children killed in the Sandy Hook massacre. She’s written a book about coming to terms with the tragedy, and the interviewer asked her to read a passage. Here’s part of what she read, about how she came to the point where she felt she could forgive Adam Lanza, the shooter:

I would never fathom what was in his heart but God could. God knew how to hold him accountable. God knew how to judge him. That burden was not for me to carry. Rather it was for me to lay down at God’s feet. It was not something I needed to grapple with the rest of my life. I didn’t have to judge. I didn’t have to figure it out. As I made this decision a burden so deep and so heavy that it nearly crushed me was physically lifted from me.

At that point my plan for today’s post changed.

The interviewer pointed out, and the mother agreed, that forgiveness isn’t necessarily something you do for the other person so much as it is what you need to do for yourself. Particularly in a case such as this one, where the perpetrator of the wrong is dead, there is no way to hold him to account anyway. And the mother of Adam Lanza, the one person on earth who might have been able to stop him, is also dead. Was she at fault in the way she dealt with her son’s mental issues? One article says that she stopped giving him his anti-anxiety medication and scheduling followup visits with the nurse who prescribed it, but, again, there’s no way to figure it out, no way to somehow go back and make her do things differently.

I was talking with a friend yesterday about this very idea that there’s no way to change the past. While we weren’t talking about a tragedy, the principle is the same: You can’t move forward into the future, not in any meaningful way, until you’ve recognized that the past is past. But that recognition can take a long time. And letting go of the past doesn’t mean forgetting about it. Alissa and her husband met with Adam Lanza’s father in an effort to understand Adam better. They came away from that interview with sympathy and understanding toward the man who has been left behind to deal with the fact that his son carried out one of the worst school mass shootings in US history.

So the families and friends and colleagues of the victims (there were six teachers killed along with the 20 children) and of the shooter are left to deal with the aftermath as best they can. Many other stories came crowding into my mind as I wrote this, in particular the book by Sue Klebold, the mother of Dylan Klebold, one of the Columbine shooters. She’s been living with her memories for 18 years as of tomorrow, April 20. I’m a little ashamed of myself as I think about my reaction when I first heard about that horror: “Why didn’t the parents know what their sons were up to?” Somebody needed to be blamed, obviously, and the shooters themselves were no longer alive.

I spent a fair amount of time this afternoon reading about the Sandy Hook tragedy; there’s a long article about the father in the New Yorker that is especially affecting. And in the midst of all this suffering and struggling to deal with the unimaginable, there’s the utter vileness of people such as Alex Jones who tried to sell the idea that Sandy Hook was a hoax, put on by “the government” or “the CIA” in order to have an excuse to take all our guns away. I cannot begin to fathom how someone can exploit such a tragedy for their own ends, but it’s not a rare thing, unfortunately, for Jones or for anyone else. I mentioned recently in a political post that Jones freely admits about 35% of what he says is solely for the purpose of riling up his listeners; he knows perfectly well that much of what he’s saying simply isn’t true. But his audience isn’t that discerning. (Not only has Jones consistently tried to make real tragedies into fake ones—he’s a card-carrying member of the 9/11 Truther movement—but he has also tried to make fake tragedies into real ones, most recently in the Pizzagate idiocy.) I ran across a recent article saying that Jones’ wife is suing him for divorce and wants him declared an unfit father so that she gets sole custody of their children. As evidence for this unfitness, her lawyer has submitted hours of recordings of the InfoWars talk show that Jones hosts. But, Jones says in rebuttal, he’s just “playing a character.”

Well, I’ve come a long way from the original intent for this post, but I’m sure what I ended up writing is much more worthwhile. Do you have a burden that you’re carrying around because you think it’s your job to make someone pay for a wrong? How can you step back and see the truth of the matter?