My husband and I have been watching a series of videos hosted by Dr. Stephen Meyer about Christian apologetics (link is to a website that markets the DVDs but not an affiliate link). Lots of really great stuff, but in this post I’m focusing on just one little throwaway line from the session we watched most recently: “Everybody’s bluffing.” Meyer had foolishly raised his hand in a lecture class at Cambridge University and

My husband and I have been watching a series of videos hosted by Dr. Stephen Meyer about Christian apologetics (link is to a website that markets the DVDs but not an affiliate link). Lots of really great stuff, but in this post I’m focusing on just one little throwaway line from the session we watched most recently: “Everybody’s bluffing.” Meyer had foolishly raised his hand in a lecture class at Cambridge University and

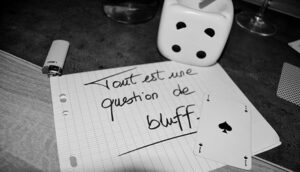

said that he was having a hard time understanding the speaker’s concepts; could Meyer get a recommendation for additional reading? Everyone stared at the brash American who was publicly asking for help. What nerve! Afterwards, Meyer’s adviser, who had observed the incident, pulled him aside and said, “You have to realize that everybody’s bluffing here, and you have to do that, too. Pretend you know what you’re doing, and if you have questions, come and ask me about them in private.”

Meyer doesn’t go on to say how he reacted to this advice; as I say, it was just a throwaway line. But it really struck me (obviously more than the actual point he was making, since I don’t remember what came before or after this statement) was how counterproductive that advice from Meyer’s adviser really is. We should all go around pretending that we know more than we do? We should constantly be putting on an act? Boy, if that isn’t a recipe for an unhappy life I don’t know what is!

So I’m sitting here pondering this idea on Thanksgiving morning, and here’s what I think:

There’s a huge difference here between putting a smile on your face and moving ahead even if you aren’t sure you know what you’re doing vs. being a total fake. As we all know, you can get away with just about anything as long as you exude confidence. (I have never mastered this skill.) You don’t have to tell people that you don’t know something; just act as if you do. If you make a mistake in a performance, give yourself some slack by realizing that your audience doesn’t know what it was supposed to sound like anyhow. Etc. You don’t have to explain or apologize, most of the time.

But—if you do move through life with confidence, if you refuse to apologize for mistakes that don’t require it, then your admissions of ignorance or failure will be much more graciously received when you do need to make them. Does that make sense? It’s in the ballpark of the “boy who cried wolf” syndrome. If you’re always putting yourself down and pointing out your errors for all to see, then a truly needed request for help won’t be treated very respectfully. You’ve set yourself up in others’ eyes—and, more importantly, in your own—as this anxious, needy person who’s always whining.

So maybe I’ll give that Cambridge professor half credit. Sometimes you do need to bluff. What would have happened during my teaching days if I’d stood up in front of my classes each day and said, “You know, I’m not really all that prepared to teach this class.” Was that true at least some of the time? You know what it was! But admitting my lack of preparation would have been very bad pedagogy. However, when I was asked a direct question to which I didn’t know the answer I made it a practice always to admit my ignorance. (I also usually said that I’d try to find the information, something I very rarely did.)

Well, I need to get the green bean casserole made, so I’d better bring this to a close. (No canned beans and mushroom soup for me! Fresh on both counts, with real heavy cream in the sauce. Yum!http://www.nationalreview.com/article/454010/thanksgiving-ten-years-ago-remembering-iraq-deployment-daughters-birth)

Y’all have a great Thanksgiving!