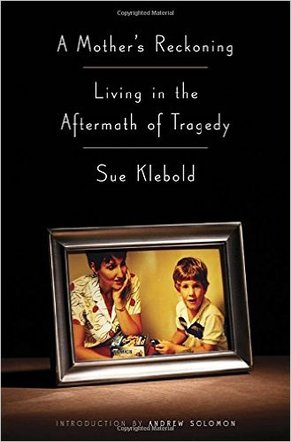

A Mother’s Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy by Sue Klebold, Crown Publishing, available in several formats on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and many other sources (including, I am told, at Costco). Visit the author’s page at AMothersReckoning.com. She has also given numerous interviews since the book’s publication which are available online. All of her author’s profits are being donated to organizations dealing with mental health issues.

A Mother’s Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy by Sue Klebold, Crown Publishing, available in several formats on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and many other sources (including, I am told, at Costco). Visit the author’s page at AMothersReckoning.com. She has also given numerous interviews since the book’s publication which are available online. All of her author’s profits are being donated to organizations dealing with mental health issues.

Doesn’t much sound like a book to be featured on a happiness blog, does it? And I would have to say that I’ve been haunted since reading this book, as

Sue Klebold does such a masterful job of describing her mental and emotional world in the years since April 20, 1999, the day that her son, Dylan, and Eric Harris walked into Columbine High School and started shooting students and teachers before turning their guns on themselves.

How could such a thing happen? Everyone weighed in at the time, with a substantial number of commentators and people on the street saying the same thing: The parents should have known. The parents must have known. How is it possible that they didn’t know?

David Owen, who writes about home improvement, family life and golf: He shut himself up in his room and wrote completely sincere poetry about how nobody loved him.

Ann Hodgman, his wife, who writes for children and young adults and whose very funny cookbooks are quoted frequently over on my hospitality blog: One of her books is called How to Die of Embarrassment Every Day. To quote from her introduction: “This book only goes up through the sixth grade. After that my life became so embarrassing that writing it down would have caused the pages to burst into flame.” (Yes, her wording is amusing. But the remembered pain is real.)

Perri Klass, now a successful pediatrician and writer, whose mother says about her:

She was a miserably rebellious adolescent, who not only closed her bedroom door to keep us out (me, mostly—in those years she preferred her father) but also erected a huge Chinese screen inside. She needn’t have bothered. I couldn’t make it over the wreckage on her floor anyway. She has thick, luxuriant, curly brown hair, and she chose to wear it long, tease it, and conceal her face under it for about five years once she hit puberty. She also decided to completely reject the boring conventional high school, to which she would not go. (xxii)

Molly Wizenberg, who now writes a great food blog, has two books to her credit, and runs restaurants in Seattle with her husband (I’d better not put the number, because it seems to constantly change): Had many issues during her adolescence, including social awkwardness and anxiety, and struggled to find her way after her father’s death.

If any of the foregoing had gone on to some sort of tragic outcome, these descriptions would have been used as explanations for why. The parents pretty much left their kids alone to work through their problems themselves. One of the above (Ann Hodgman, I think) says that she is unspeakably grateful that her parents didn’t pry too much. She was allowed to retreat to her room, even to eat her meals there. Was that the right thing for her parents to do? Well, she says so.

On the other hand, while Dylan had his issues and ended up getting arrested (along with Eric Harris, the other shooter) his junior year for breaking into a van and stealing electronics, he had friends, was well liked, had a job, was in the gifted program at the school, attended the prom three days before the shootings, was heading off to college . . . on and on.

Two strands run through the book: I should have known, and I didn’t know. I should have been able to prevent this, and I couldn’t have prevented it. Over and over Sue asks herself “the question that would bedevil and perplex me, and ultimately animate the rest of my life: ‘How could you? How could you do this?’”

She has obsessively gone over every detail of Dylan’s life leading up to the massacre, sifting every interaction for clues. Especially chilling are her memories of that morning, when Dylan got up early and left the house without talking to her, only shouting out “Bye!” as he slammed the door. That was the last word he ever said to her. She felt uneasy, hearing something in his voice that troubled her, but what should she have done? Run after him and asked him what was the matter? Followed him to school? Now, in retrospect, those actions seem perfectly legitimate, but at the time it would have seemed absurd. Søren Kierkegaard said, “Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.”

So why should anyone read this book? While Sue has dedicated her life to organizations that investigate the causes of mental illness and that help grieving parents of suicide victims cope, there are no ultimate answers given. How can anyone think that the professionals have the answers, when Dylan was given early release from the diversion program he had to attend after his arrest and Eric was given a glowing recommendation by one of the psychologists? They fooled everyone.

Well, almost everyone. One set of parents who knew about Eric’s violent website tried repeatedly to warn the school about his problems, but no one listened. There were teens who knew that the boys were buying guns, but no one spoke up. Once the boys had moved from talk to action authorities could have stepped in, but they did not know to do so. I guess one lesson here is that the way to a happy life is most assuredly not to stick your fingers in your ears and sing loudly. The people you love and trust the most may betray you and everything you stand for. (It has always amazed me that a spouse can carry on an affair and keep it a secret, coming home and interacting with his or her family in a completely normal-seeming way.)

I was reminded of a verse in the book of Jeremiah: “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: who can know it?” (17:9 KJV). But the next verse goes on to say: “I the Lord search the heart, I try the reins, even to give every man according to his ways, and according to the fruit of his doings.” There is a final reckoning to come, and there is no escape from it.

But I would say that this book is ultimately a story about love: a mother’s love for her son, no matter what he did. Without love, she would have no pain. C. S. Lewis puts the idea this way:

Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.

People often say to loss survivors, “How do you make it through the day?” There can be a smugness in that question, almost an implied accusation: “How could you make it through the day? I certainly couldn’t.” And then tragedy strikes in your own life and you realize that there’s no real choice: You have to make it through the day. People are counting on you.

So we should never, ever say to someone, “I know just how you feel,” because that’s not possible. If you read this book, though, you will get a searing glimpse into someone’s heart. How easy it is to wound someone who is already devastated! And how comforting the smallest kindness can be. If nothing else, that one lesson is enough of a reason to experience this tragedy through Sue Klebold’s eyes.

Outstanding post! Deep food for thought…

Two things you say I want never to forget:

How easy it is to wound someone who is already devastated…

How comforting the smallest kindness can be.

Thank you, Debi

Wow, I am going to read this book. Thank you for recommending it!

Great review! I’ll read the book, thanks for posting. What book did C.S. Lewis write his quote in?

Lewis’s comment is from his great book The Four Loves.

Great post, Debi. Thank you for taking the time to write this. I will get this book.