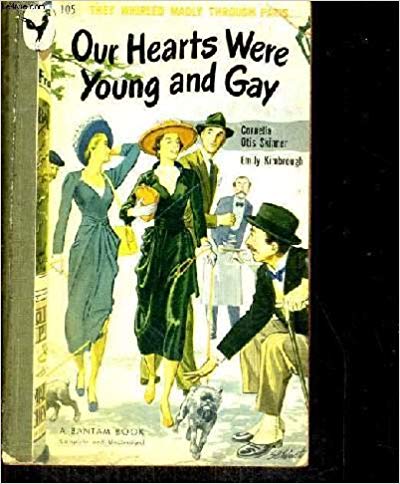

Our Hearts Were Young and Gay

by Cornelia Otis Skinner and Emily Kimbrough, originally published in 1942, now available in many formats. France in the Twenties is a charming place, and the authors are charming, too.

I was reminded of this book (how many of my reviews start that way?) while I was writing some travel tips based on our recent trip to France. One of my recommendations, passed on from Rick Steves, Mr. European Travel himself, was to wear a money belt. His statement brought to mind the so-called “security pocketbooks” that Cornelia and Emily were forced to wear during their own trip to 1920’s France. This was, of course, during the days before women wore pants very much, and while they weren’t wearing layers of petticoats their skirts were longish and baggy. So see if you can picture this: an elastic belt around the waist with a narrow band attached to it hanging down and a purse thingy attached to that, dangling between the wearer’s legs. As long as you stand still or walk slowly the thingy should be unobtrusive, but if you’re at all active it will start swinging. There’s a very funny scene early on when Emily and Cornelia are dancing (I think it’s onboard their ship) and their purses start bumping into the knees of their dancing partners. Both girls exit the dance floor looking embarrassed, followed by their partners who look puzzled.When I directed the theatrical version of this book for a high-school play, those purse thingies were the bane of the cast’s existence as they were always getting lost. On the night of the performance the poor girl playing the maid at the hostel was supposed to find the purses hidden under the mattresses in the girls’ room where they’d deliberately left them behind. The last line of the play was supposed to be “Mademoiselles! Mademoiselles!” as the maid rushed after the girls with the hated objects held high. Alas! The hated objects weren’t there. The maid was forced so simply run off, shouting her line, without anything in her hands. The audience sort of laughed, but it wasn’t at all clear what they were supposed to be laughing at. And the curtain rang down. Sigh.

Anyway, back to the book. One element, something I hadn’t thought about before, is that it was written during the early years of World War II, with a publication date of 1942. While I haven’t been able to document when the actual writing took place, certainly while the whole editorial/publishing process was going on there had to be an awareness that those pleasant scenes of the French countryside and those descriptions of the glories of Paris were being overshadowed by the war. There was fighting in those fields and those streets. I kept reminding myself of this fact when we were in Normandy back in June. It was very difficult to sit there (as we did all afternoon) waiting for the parachute re-enactment and imagine gunfire being exchanged between desperate men. The time span was even shorter for the writers of the book, of course. So it’s good for the reader to keep the historical time frame in mind, as this recognition adds a note of poignancy to the lightheartedness of it all.

There are some brilliant scenes in the book: Cornelia’s bout with the measles that almost lands her in quarantine as the boat lands in France; Cornelia’s bout with the bedbugs after sleeping in an elaborate historical four-poster bed; Emily’s heroic effort to save a drowning man that results in her hitting him with a thrown deckchair. But even in the midst of all these high jinks there are moments of seriousness. When the girls join village dancing in the streets on Bastille Day they notice a lovely young woman wearing a cape. She’s very popular, dancing with one man after another. A gust of wind blows her cape aside and the girls see that her arms end at the elbows with small rudimentary hands attached. Later on they see various offerings hanging before the altar in a local church; one is a pair of beautifully-modeled clay hands hanging from a ribbon. Emily and Cornelia figure that the hands have been placed there by the young woman’s parents. (I just looked up the young woman’s condition; it’s called “phocomelia.” Before the thalidomide scandal in the 1960’s the condition was extremely rare.) For me, the most touching scene in the book is the one that takes place in Rouen, the city where the trial and execution of Joan of Arc took place. Here’s the passage:

Suddenly, miraculously, we were in the Middle Ages, or rather, le Moyen Age. Past the Palais de Justice and down the rue Jeanne d’Arc, under the Tower which also bears her name, where her pitiful trial took place, and then at last we were in the Old Market Place, standing on the spot where that guileless girl from Domremy was burned to death. It was Emily’s first experience of the sort. She stood in the center of that beautiful and heartbreaking square murmuring, “This is the place. This is the very place.” And quietly, unpremeditatively, we both stooped down and touched the cobblestones, We were moved to the point of wanting to burst into loud sobbing. For all our conscientious sight-seeing there had, up to now, been a certain deliberately planned quality to our appreciation. Our response to things, while enthusiastic, had been anything but hyper-sensitive. But we responded now to Joan of Arc, a girl of our own age. We responded with all the warmth and ache of our young hearts. This was what we’d come abroad for, this breathless moment, when we put down our hands to touch the spot where a momentous and agonizing hour of history had passed. (pp. 151-152, accessed via Internet Archive.)

I will spare you the account of my attempt 40 years ago to have the same experience; we will just say that the Rouenais were busily turning the historical spot into an elaborate memorial and had therefore blocked off all access to the construction site. Honestly! We ran out of time on our recent trip to visit Rouen but are planning to go back in three or four years to celebrate my 70th birthday. I don’t think the original cobblestones are going to be very much in evidence, though.

There are some interesting cultural notes, such as Cornelia’s and Emily’s taken-abackness when two black gentlemen are seated at their table in a pension. The book is a time capsule in such ways. But, as I think you can probably tell by the passage quoted above, there’s real heart in it. Get hold of a copy and take it along with you on your own next trip. (I accessed an excellent audio version from my library which is available on Amazon but is very expensive.) You’ll fall in love with Emily and Cornelia—I promise!

This post contains affiliate links. If you click through and purchase an item, I will receive a small commission at no additional cost to you.